Tyler Dawson

Published:December 30, 2021

-National Post

In January 2001, an open letter appeared on the front page of the National Post. It was addressed to Ralph Klein, and urged the then-Alberta premier, just months after Jean Chrétien won his third federal Liberal majority, to “build firewalls around Alberta,” to protect against “an increasingly hostile government in Ottawa.”

The writers of the “Alberta agenda,” seven prominent Alberta conservatives and academics, listed five ways the province could wrest certain powers away from Ottawa. Among the suggestions were a provincial police force to replace the RCMP and an Alberta-only pension plan.

Klein was no Ottawa-hugging liberal. Once, as mayor of Calgary in the 1980s, he warned of “creeps” and “bums” flocking in from Eastern Canada. Still, he rejected the proposals. “The sense of defeatism that underlies the notion of building a ‘firewall’ around this province is unnecessary,” Klein responded. “Albertans are strong Canadians…. We have much to offer other Canadians, and in turn, there are lessons we can learn from other Canadians.”

Ted Morton, a University of Calgary political science professor, was one of the authors of the Alberta agenda, and would go on later to become the province’s finance minister. He doesn’t believe the sentiment that inspired that letter, the feeling of alienation towards Ottawa, has gone away.

“The disillusionment with the status quo is deeper and wider than it was 20 years ago. And it’s also better articulated and better funded than it was 20 years ago,” Morton said. “I think there’s a deep sense that what my generation of reformers, in the small-r sense, tried — the Reform Party with Preston Manning, Senate reform, getting Stephen Harper elected prime minister — in the end, none of that has worked.”

It is the idea that every time Alberta’s interests need to be met, they’re ignored or countered

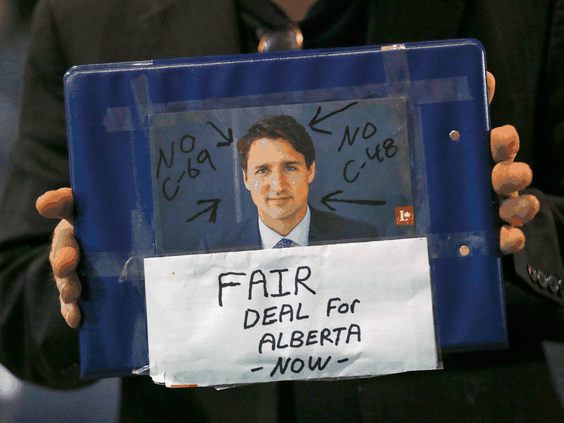

Twenty years later, some of the agenda’s ideas are starting to influence Alberta government policy, the result of the work of the United Conservative government’s “ Fair Deal Panel ,” which canvassed the province in 2019–20 to hear out Albertans’ feelings of discontent toward a federal government that many feel treats the province unfairly, perhaps even more so now than at the time of the Alberta agenda.

The panel, when it reported in 2020, made 25 recommendations. Some went further than the Alberta agenda, suggesting Alberta push, for example, for “resource corridors” across the country, and that the province take legal action against damaging federal legislation. It suggested the province hold a referendum on equalization . And, taking cues from 2001, the fair-deal panel also revived calls for a provincial police force, provincial pension plan and for Alberta to collect its own income tax, the way Quebec does (something the government notes requires “significant further analysis”).

“It does seem like they’re old solutions, but like, the fact that they’re still around is emblematic of the fact that the problems are very similar, and that the solutions haven’t been undertaken,” said Josh Andrus, executive director of Project Confederation, which builds grassroots support for fair-deal-style measures. He says his new generation of conservative Albertans is experiencing “the same undercurrent of frustration” as previous ones.

The province says work is underway on 12 of the 25 recommendations, and the equalization referendum was held this past October, with a majority of those Albertans who voted saying they wanted the principle of equalization taken out of the Constitution. For some long-frustrated Albertans, it feels like the developments since 2001, most notably the last few years under the Trudeau Liberals, have made more people feel that the time has finally come for a firewall — or maybe something stronger.

“I hate to say we wasted the last 20 years,” Morton said. “Maybe it took the experience in the last 20 years to expand support for not necessarily separatism, but certainly for greater autonomy, it took that experience to expand support for that from a small number of people, which we were in 2000, to something close to a majority today.”

In May 2021, the University of Alberta’s Common Ground project released polling into feelings of alienation in Alberta and Saskatchewan. It found 62 per cent of Albertans believe the federal government treats Alberta worse than other provinces, and 67 per cent believe Alberta doesn’t get the respect it deserves.

“A lot of Albertans feel like the rest of Canada doesn’t understand or appreciate the contributions that they’ve made to Confederation,” said Jared Wesley, a political scientist at the University of Alberta, who worked on the research.

That isn’t entirely new. Paula Simons, a former journalist appointed as an Alberta senator by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, says that “for better or worse, and often for worse, the culture of grievance is baked into the DNA of this province.” In the 19th century, western farmers protested federal railway freight rates and punitive tariffs meant to force east-west trade. In the 20th century, there were the eastern banks that bailed on Alberta during the Great Depression, the forced grain sales to the Canadian Wheat Board and the National Energy Program (NEP) that killed an investment boom in the province by forcing Alberta’s oil producers to ship oil to Eastern Canada at below-market prices.

“Even if people can’t mention one specific issue (fuelling their frustration) … it is the idea that every time Alberta’s interests need to be met, they’re ignored or countered,” said Faron Ellis, a Lethbridge College political scientist. But he thinks a big part of the current frustration can be traced back to the damage to Alberta’s industry inflicted by the Pierre Trudeau government in the 1980s with the NEP, which echoes through his son, Justin Trudeau, who is seen as hostile in his own way to the province’s energy sector.

If you ask an Albertan to draw a picture of a typical Albertan — Common Ground researchers did just that in 2019 — 18 per cent would sketch an oil and gas worker. “There’s no question that oil and gas forms a part of Albertans’ collective identity,” said Wesley.

In 2017, when Trudeau said Canada needs to “phase out” Alberta’s oilsands industry, many saw it as a direct attack on the province’s livelihood. This government’s agenda, focused as it is on fighting climate change, is seen by many as outwardly hostile towards Alberta, the country’s largest emitter. The Liberal government has created a new — and some say onerous — system of environmental regulations for major infrastructure projects, and has banned potential future export opportunities, such as shipping crude oil from northwestern B.C. In recent years, billions of dollars in investment have been lost to Alberta.

As recently as October, Trudeau, along with nearly 300 hangers-on, flew to Scotland for the COP26 climate change conference. In his five-minute speech to the audience, Trudeau boasted about the Liberal carbon tax and vowed that Canada would move to put strict caps on emissions from the oil and gas sector — singling out Alberta’s industry alone yet further restrictions. “This is no small task for a major oil-and-gas-producing country,” Trudeau declared.

The feeling of having its economy hemmed in is what leads to much of the anger in Alberta over equalization — a sense that Albertans pay heavily to subsidize the rest of the country, while getting attacked in return.

The fiscal balance — that’s how much money Alberta sends out of province in taxes, compared to what it gets back in transfer payments — is heavily skewed against Alberta, largely because it’s such a wealthy province. Between 2010 and 2018, Albertans contributed about $5,000 per person, while Quebecers received $1,979 per person, on average. Yet it was Quebecers who made a show of protesting TransCanada’s Energy East pipeline that would have brought Alberta’s oil from Hardisty, Alta., to Saint John, N.B. When TransCanada, now TC Energy, gave up on the Energy East project in 2017, it cited regulatory hurdles, which the Liberal government had made, in making the decision. The Trudeau government, in contrast, claimed it was a business decision based on changing markets.

Quebec Premier François Legault, in 2018, said there was no “social acceptability” for Alberta’s “dirty energy,” even as the money made by that oil helped pad his province’s budget.

“(The feeling is) that Albertans have contributed in good times and in bad times to the rest of Canada, and are only asking for help with economic developments. In other words, get out of the way of our pipelines,” explained Wesley.

Donna Kennedy-Glans, a former provincial cabinet minister, who also served on the fair-deal panel, believes climate pressures have been a “spark for the relighting of … frustration” and that some Albertans feel like “scapegoats” within the climate change discussion.

As a result, says Wesley, it’s not just a feeling of Alberta versus Ottawa, anymore, but Alberta versus the international forces at the UN and COP26, among U.S. Democrats, and among activists pushing a decarbonization agenda.

“We talked to people in focus groups and they’re saying ‘we not only have to fight Ottawa, we have to fight Greta,’” Wesley said.

Alienated Albertans see the connection in a federal government that seems unconcerned with defending the interests of fellow Canadians and aligning instead with those who want to see the province’s primary industry shut down. That, in turn, is helping drive support for outright separation, an option that so far a minority of Albertans would consider (around 20 or 25 per cent, according to the most recent polls), but one that has been growing in recent years.

In 2017, Trudeau told an audience of energy industry leaders in Texas that “No country would find 173 billion barrels of oil in the ground and just leave them there.” Despite the fact the Liberal government bought, for $4.5 billion, the TransMountain Expansion project, which runs from Edmonton, Alta., to Burnaby, B.C., there’s the widespread perception Trudeau has offered little defence of Alberta oil.

And when U.S. President Joe Biden on his first day in office this year cancelled the previously approved Keystone XL pipeline to the U.S., Trudeau did not complain, noting only that he was “disappointed.”

“Ideally, we’d like to see Ottawa defend that Alberta’s interest is also in Canada’s interest,” said Morton. “If Alberta’s going to have a future — and that future does depend on economically competitive access and global prices — and if that can’t happen inside of confederation or within existing institutional arrangements, then … will Alberta fight for a future that does ensure that?”

While an Alberta-run pension plan wouldn’t do much to change approvals rules for oil projects or secure a new pipeline route, some of those who support measures that would give Alberta more autonomy believe such fair-deal recommendations could actually help tamp down western separatist sentiment. While so far separatism hasn’t organized especially successfully, the 2019 Wexit movement spawned a political party, and did mark the extent to which the sentiment had spread.

“In 2019, Wexit was filling rooms. …There’s a lot of people who’ve given up on the concept of remaining in the country,” Andrus said. “The hope is that by alleviating some frustrations and grievances that we can help fix the problem or at least minimize it.”

But Leah Ward, who worked as an issues manager for former NDP premier Rachel Notley, thinks that conservatives who dominate the alienation discussions have it backwards. “There are good reasons for Albertans to feel disconnected from the rest of Canada and it’s not helped by national policies that disproportionately affect Albertans,” Ward said. “The solution to that isn’t to stoke up discussions about separation. I think a more productive conversation is in which ways can we participate more in Confederation, right? So, basically, the opposite.”

Alberta’s current premier, Jason Kenney, is a former federal cabinet minister known to have deep affection for the federation. He’s been outwardly cool to any talk of separation, while arguing that Alberta can play a more assertive role within a stronger federation. “I do think there is value in pursuing a federalist version of Quebec constitutional strategy in the past 50 years,” the premier recently told the National Post.

With the fair-deal panel, “(Kenney’s) realizing, if you want to actually get something done, you shouldn’t talk about things where you need someone else’s permission,” says Ken Boessenkool, an original signatory of the Alberta agenda, and a professor at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. Boessenkool said that when the seven signatories sat down to write the letter, including Stephen Harper, who would become prime minister five years later, that’s the argument they were making: that the measures to give the province more independence from Ottawa should be options for the Alberta government to pursue unilaterally. That’s part of the benefit of a pension plan proposal, or a provincial police force. It’s also why other proposals, such as equalization reform or creating an energy corridor, are far more challenging.

These latter strategies “require a great deal of dialogue and upfront commitment by all provinces,” said Kennedy-Glans in an email interview. “An individual province can table those ideas but can’t impose them on others. And how you come to that negotiating table — elbows up, or elbows down — matters.”

While separatism remains a minority viewpoint, doubtless a larger number support some variety of a “fair deal” for Alberta.

Preston Manning founded the Reform party in the 1980s on the platform “the west wants in,” and he thinks today’s discussion needs to shift “alienation” towards “aspirations,” including proper recognition of the importance of natural resources, as well as domestic free trade and resource-transportation corridors. These are all suggestions made by the fair-deal panel, which Manning also sat on. “It’s better to frame these issues in terms of western aspirations. Like, alienation is negative: if you harp on it too long, it sounds like whining,” said Manning.

While it seems the world will eventually become less reliant on petroleum products, the question of how quickly that will happen is a matter of perspective, and fierce debate. “There’s been a few epiphanies over the last 18 months, that the world we knew is coming to an end,” Simons said. “We must channel the energy and the entrepreneurship and the courage of Albertans into figuring out what is next, how we leverage our natural resource wealth to prepare for the new economy.”

They’re saying ‘we not only have to fight Ottawa, we have to fight Greta’

But the fact remains that oil consumption, except for a dip during the pandemic, hasn’t really stopped growing yet. And Alberta still has a great deal of it — those 173 billion barrels Trudeau mentioned — that the province wants to be free to sell.

“Without oil and gas, Calgary’s just another Regina,” said Morton. “Are we in an energy transition? Yes. But that’s not a five- or 10-year process, that’s a three- or four-decade process. And in that three- or four-decade process, the world runs on (fossil fuel) energy.”

In fact, oil prices have been climbing of late: West Texas Intermediate crude marched up from around US$20 per barrel in 2020 to US$84 in November (the price slid back into the US$70 range in December).

And history shows that the ebbs and flows of Alberta alienation — and indeed separatist sentiment — are at least loosely linked to the health of the oil and gas sector. November 2021 was the best-ever month on record for oil production in Alberta, breaking the previous record set a month earlier. It may be that what happens next in the oil and gas business, as much as anything, could decide how much fuel there is for a new Alberta agenda.

“People always asked me well, how come the Alberta agenda never happened? And the simple answer to that is, three years after the Alberta agenda, oil was over 100 bucks,” Boessenkool said. “No one in Alberta cared much about slagging Ottawa, because we were having a big party.”