By

January 18, 2022

-Fharbor

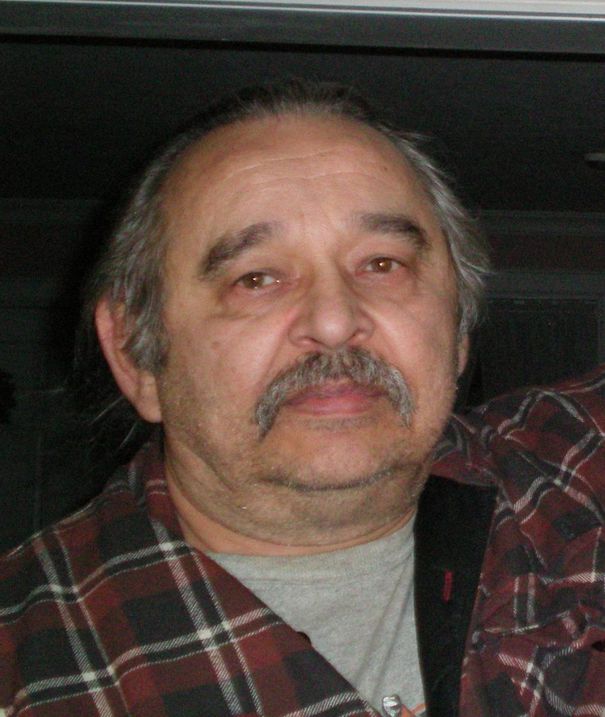

Rodger Kotanko had just returned to his rural home and workshop in Simcoe, Ont., a short drive west of Port Dover, near Lake Erie, after doing some shopping with his wife, Jessie. She’d just failed a driver’s test and needed some cheering up.

The gunsmith’s workshop, a detached garage, was where Kotanko tended to the firearms of loyal customers — police officers and soldiers among them. The garage sits at the end of a driveway, lined on one side during summer with towering sunflower plants Kotanko would never see again.

On Nov. 3, just before noon, a customer was waiting as Kotanko made his way into the workshop, likely unaware Toronto police were watching him.

Until now, what was known through official channels through Special Investigations Unit press releases is that officers were there to execute a search warrant, and Kotanko was shot dead by one officer. Seven other officers have been designated as witnesses to the events that have raised many questions in a community where Kotanko was respected.

Among them, what were Toronto police so interested in that they had honed in on a 70-year-old father of three, some two hours and a great lake away from the big city?

Search warrant documents unsealed at the request of the Star reveal why.

In short, police believed Kotanko had milled off the serial numbers on two restricted handguns registered to his company, and, without authorization, transferred their ownership, with the guns ultimately ending up in the hands of two young Toronto residents.

Kotanko’s family has also obtained the search warrant documents, and on Tuesday announced a $23 million wrongful death lawsuit, alleging, the family said in a press release, that Toronto police “unlawfully executed a search warrant and used excessive force … in a military-style take down,” shooting him four times.

The family alleges in their lawsuit that the search warrant was not presented on the day of the raid, that the information used to get the warrant “was obtained using irrelevant and prejudicial information” and was “designed to undermine (Kotanko’s) credibility and standing before the judge or justice of the peace and the public.”

Police “recklessly targeted” Kotanko and the operation was “negligently planned,” the family said in the press release.

The family also alleges Kotanko’s wife was unlawfully detained and restrained by police and prevented from “providing him with comfort after he was shot and was dying.”

The family’s statement of claim, filed this week, names five unidentified officers with the Toronto police Integrated Gun and Gang Task Force, an inspector in charge of the task force, Chief James Ramer and the Toronto Police Services Board as defendants.

“The Kotanko family is holding Toronto police to account, so this doesn’t happen to someone else,” the family’s lawyer, Michael Smitiuch, said in the press release. “Rodger Kotanko wasn’t able to defend himself, or his reputation, but his family will.”

The allegations have not been proven in court and police have not yet filed a defence document.

Toronto police on Tuesday acknowledged receiving a copy of the statement of claim from the Star but a police response was not immediately available. The police board did not immediately respond Tuesday to a request for comment.

Once a civilian-led SIU investigation is underway, police typically do not comment on a case.

The 28-page search warrant application, called an “information to obtain,” or ITO — a document put before a judge to seek authorization for a search warrant — offers a very lightly redacted account of the reasons for the police raid. The Star is scheduled to appear in court in late February to contest a police request to have names of officers and civilian employees redacted from the materials.

Otherwise, the Star is free to report its contents, which include details of the investigation that led police to Rodger Kotanko’s garage.

The Handguns

In late August 2021, a young person crashed a stolen Mercedes at Victoria Park Road and Finch Avenue East in Toronto, resulting in an arrest and the seizure of a Norinco 1911A1 .45 calibre handgun, according to the ITO.

Two months later, on Oct. 10, officers with North Bay Police Service were investigating a “possible kidnapping” when they pulled over a vehicle with three males, all with Toronto addresses. One of the males, a youth, was allegedly found to be in possession of the same brand of handgun.

In both cases, the document states, the guns’ serial numbers appeared to have been removed by a milling machine, as had other markings on the firearms’ slides.

According to the ITO, police were able to restore the serial numbers, finding the weapons had been registered to D.A.R.K. International Trading Company, one of two businesses owned by Kotanko, the other business being R.K. Custom Guns.

The markings on the slides were also restored to reveal cursive “RK” letters on both, and “RK Custom” on the North Bay gun.

A Gun ‘Savant’

In 1970, when Rodger Kotanko was just 19, he got a criminal record for “possessing a narcotic” for the purposes of trafficking and for possessing a “restricted unregistered firearm,” for which he served nine months, according to police database searches detailed in the ITO.

After that, Kotanko had no other criminal record.

For its part, Kotanko’s family says the “narcotic” was cannabis and the gun, a black-powder gun Kotanko had made — the kind, said brother Jeff Kotanko, that you would see in “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies.

“I’m not even sure the gun fired,” said younger sister Suzanne Kantor.

Kotanko had been attending forestry school at the time. The charges interrupted that. But, he clearly had a gift with firearms.

Kotanko gained a reputation for custom builds and reliability. He could charge as much as $7,000 for a custom handgun, and customers lined up for them, including competitive shooters and military clients, said Jeff, who also worked with this brother.

“He was a gun savant,” he said.

Rodger Kotanko also loved adventure, and for a time was a competitive skydiver and taught at the Simcoe airstrip.

Lately, Kotanko — who Kantor said stood maybe five-foot-six, moved “like a sloth,” and loved to talk — was working on his diet. He lived for family and family dinners, including Christmas time. While wife Jessie, who came to Canada from China four years ago, tended to the garden behind the house, Kotanko would can and make pickles of whatever Jessie grew.

“He’s not someone that you would even fear. He’s a 70-year-old man who was on the never-ending diet trying to live healthy, had had bypass heart surgery,” said Kantor. “He loved pickled beets. He loved pickled peppers. The hotter the peppers, the better they were.”

Twenty-Five Handguns

According to the police ITO, Kotanko — an experienced and licensed gunsmith with a certificate to acquire non-restricted, restricted and prohibited firearms — notified the Ontario Chief Firearms Office in March 2009 that he was importing 25 Norinco 1911A1 .45 calibre pistol frames that he would make into working firearms, with new serial numbers, which he properly reported.

The guns’ serial numbers ranged from RKC01 to RKC025. The “RKC” stood for Rodger Kotanko Custom, and cursive branding was also added to the slides.

After the two seizures, police checks with the firearms office showed 14 of the 25 weapons were still registered to D.A.R.K., including the seized guns, which bore the serial numbers RKC04 and RKC014, and were to be stored at Kotanko’s address.

In the search warrant material, the officer who prepared the document noted the length of Kotanko’s career in firearms and that he had “legally bought, sold, manufactured and successfully transferred hundreds of firearms over the years,” and that he would well know all the rules around reporting of lost or stolen firearms and transfers.

Also, being a gunsmith, the officer said Kotanko would have access to tools, including possibly a milling machine. The officer also believed Kotanko “would also be one of the few people who would have an interest in milling off the name of his company from a firearm sold to the criminal market, along with the serial number.”

Based on that, the officer formed the belief that Kotanko transferred the guns without authorization. That belief formed the basis for the search warrant. On Nov. 3, Ontario court judge James Chaffe authorized a three-week period to search Kotanko’s home, beginning that same day.

Kotenko’s brother Jeff questions the logic of police thinking. First, he said, Kotenko, of all people, would have known that you cannot effectively remove a serial number unless you remove a chunk of metal. Second, why would his brother create a crime gun when he can fetch $7,000 for a custom gun?

Jeff’s theory is that the handguns had recently been legally transferred and that the firearm computers had not caught up to the transactions. He recalled his brother mentioning a man was looking to buy a pair of the handguns for him and his son. A logbook Kotanko kept was seized in the raid and would be where his brother kept information about authorized transfers, said Jeff.

As well, every couple of years, said Jeff, the Chief Firearms Officer conducted checks to ensure all of the many firearms Kotanko kept on-site were accounted for. The last check, conducted pre-pandemic, found nothing amiss, said Jeff.

The Raid

Kotanko’s wife failed her driver’s licence test on the morning of the raid. Kotanko had bought her a car to help her socialize, and he was working on his Cantonese. Disappointed by the failure, the two went out shopping.

While out, a customer called and said he was coming by the shop.

Police were nearby upon Kotanko’s return home and the customer and Kotanko were in the garage when the raid went down. Police, note the family in their statement of claim, arrived with their own ambulance in tow.

The gunsmith was killed in a place where Kotanko, in the words of sister Kantor, loved to “shoot the s—” with customers over Tim Hortons coffee while he worked on their guns. It was also a pace where he had loved to debate with Kantor’s daughter, who had died suddenly of a heart problem just nine months earlier.

Among the family’s questions: Why wait until Kotanko had returned to his shop, where his hands are on guns almost all the time?

“We don’t get it,” said Kantor. “It wasn’t like he was some evil person. He just wasn’t. We just want answers. It’s terrifying to think that this can happen.”

The SIU investigation into the killing continues.