January 11, 2022

-CBC

A new public health order that leaves it up to employers to decide which Albertans infected with COVID-19 should go to work is short on oversight and enforcement, health law experts say.

The “critical worker exception” order lets employers judge, with few conditions, whether the service they provide is critical and which of their COVID-positive employees are essential.

It was enacted Jan. 3 — just days after Health Minister Jason Copping announced the change, along with plans to cut Alberta’s mandatory isolation period from 10 to five days. Details of the order, which Alberta Health describes as a last-resort measure for critical services, were made public last week.

“This order is unique in its stupidity, and unique in terms of its just sheer disregard for workers’ rights,” said Ubaka Ogbogu, an associate professor in the faculty of law, and the Katz Research Fellow in Health Law and Science Policy, at the University of Alberta.

Critical workers who are symptom-free or have mild symptoms can be called back to work.

There is no application process for the exemption, and return-to-work plans will not be reviewed by any government department. The order, signed by Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. Deena Hinshaw, does not provide a list of eligible sectors.

“What’s really scary is that it’s the employer who determines if they have met the standard,” Ogbogu said. “There is no process.”

“I can see it being used by a variety of industries that are not necessarily essential.”

The order is not designed to protect public health, but to insulate industry from the impacts of the pandemic, Ogbogu said.

“It’s quite appalling that the chief public health officer would decide that you’re not sick enough to be home, but not well enough to be at work without mitigation.”

Last resort

In a statement, Alberta Health spokesperson Christa Jubinville said the decision to bring infected workers back should only be made as a last resort to maintain services which, if disrupted, might endanger the public.

The decision to provide the exemption was based on evidence that fully immunized people have shorter infectious periods, Jubinville said.

“The workers and worksites to whom this exception may apply are very limited,” she said.

“Workers must be required for in-person operations, and be in a position where there is highly specific training and/or very few individuals who are able to complete the required tasks.”

To qualify, a worker must: be part of a service of which a disruption would be harmful to the public, and, be determined by the owner or operator to be needed in-person for duties that are essential to the continued safe operations of the service.

Managers must also develop a safety plan to minimize the risk posed by COVID-positive employees.

Workers deemed essential are only allowed to leave isolation to complete their job duties. Employees should remain masked when in contact with others and, whenever possible, work alone.

The order also details a “risk hierarchy” for determining which workers should be called in. It states that preference should be given to workers who have three doses of vaccine, with unvaccinated workers being selected last.

Jubinville said there will be no targeted inspections but infractions may be noted if the businesses are inspected for other purposes and followed up on as required.

“Should non-compliance occur again or if it is particularly egregious, penalties for breaching isolation rules may be imposed.”

Ogbogu says the province should establish an application process for employers and a complaints process for affected workers.

He noted that the order mimics guidelines recently issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that have been widely criticized by the American medical community.

Lorian Hardcastle, an associate professor in the faculty of law at the University of Calgary, said more oversight is needed to ensure workplace safety is maintained.

“I’m confused as to how the government took evidence that the infectious period can be shorter to mean that there’s no infectious period at all,” said Hardcastle.

“It’s hard to claim that working conditions are unsafe where they’ve been sanctioned by the government through a public health order.”

The province should have also created an exhaustive list of which operators qualify and established an application process to ensure each worksite safety plan is reviewed by the chief medical officer of health, Hardcastle said.

Inspections should be mandatory, she added.

“Both of those things would have helped satisfy the concern that it’s going to be a bit of a Wild West in terms of which businesses decide that they qualify.”

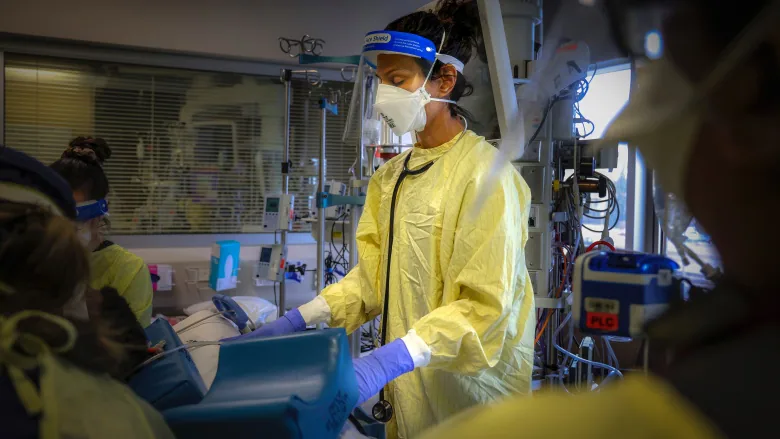

As Omicron continues to spread, the strain on frontline health-care is already being felt.

Alberta Health Services is beginning to see more workers off sick, spokesperson Kerry Williamson said in a statement to CBC News.

“This is now beginning to impact some health-care services, particularly some acute care services at rural sites where staff illness or isolation is leading to staffing challenges,” Williamson said.

If capacity becomes overwhelmed, AHS will redeploy staff. Services and surgeries could also be cut back, Williamson said.

“We know we will see increased sick rates in the days ahead as Omicron spread continues.”