The Canadian Press

March 13, 2022

-CTV

HALIFAX –

Repeated communication failures were partly to blame for the Nova Scotia RCMP’s inability to stop a gunman from killing 22 people over a 13-hour span in April 2020, recently released documents show.

Transcripts of interviews with two Mounties who helped co-ordinate the police response reveal that key information about the killer’s vehicle — a replica RCMP cruiser — was not relayed to senior officers or was ignored.

The documents released by the public inquiry into the mass shooting point to other shortcomings, including shoddy technology, erroneous assumptions about the killer’s whereabouts and delays in warning the public.

Among the first senior Mounties called in the night of April 18, 2020, was Staff Sgt. Allan Carroll, district commander for Colchester County and a 39-year veteran of the police force.

“It was one of the worst nights of my life,” Carrol said during an interview with inquiry investigators on Nov. 10, 2021.

Soon after he arrived at the detachment in Bible Hill, N.S., some time after 10 p.m., Carroll said he and another senior Mountie quickly learned from 911 calls that a lone gunman in Portapique, N.S., identified as Gabriel Wortman, was shooting at people and setting fire to homes.

They were also told he was driving a mock police car.

Based on the information he received, Carroll said he understood the suspect was driving an old, decommissioned police car that had no markings.

“And that’s what we heard, old police car,” he told the investigators. “(An) old unmarked old (Ford) Taurus. There was a bunch of them around.”

But that’s not what witnesses in Portapique were telling 911 call-takers. Previously released 911 transcripts clearly show that the killer’s first victim, Jamie Blair, described the car as “decked and labelled RCMP.” And shortly after she was fatally shot in her home at 10:04 p.m., her 11-year-old son — who survived the mayhem — told 911 the vehicle was “just like a police car,” complete with emergency lights and proper decals.

At that point in the police operation, Carroll was joined by Staff Sgt. Addie MacCallum, district commander for neighbouring Pictou County. Like Carroll, MacCallum said he understood the suspect’s vehicle was an “old police car.”

MacCallum said that when he arrived at the detachment, his priority was to get an overview of what was happening in Portapique. But he said it took him half and hour to find a computer with the RCMP’s Computerized Incident Dispatch System, which uses satellite tracking to show the positions of police vehicles.

Despite the high-tech display, MacCallum said the digital map was lacking.

“I’m looking on the screen where the members are, but I’m not very happy with what I’m seeing,” MacCallum, a 23-year veteran, told inquiry investigators on Nov. 5, 2021. “I start trying to find better mapping because I’m trying to see what we have for escape routes.”

MacCallum tried Google Earth, but he quickly realized the site was “making roads where there’s no roads.” The officer then recalled all detachments are supposed to have access to a licensed program called Pictometry, which offers access to high-resolution aerial photographs.

“I couldn’t find it, and Al didn’t know where it was,” he said. “So we ended up pulling a map off the wall.”

Carroll, who at the time was a month away from retirement, later told investigators he was never trained to use Pictometry.

Using a road atlas and other maps, Carroll and MacCallum concluded there was only one way for a vehicle to get out of the darkened, rural enclave where the shooting started: Portapique Beach Road.

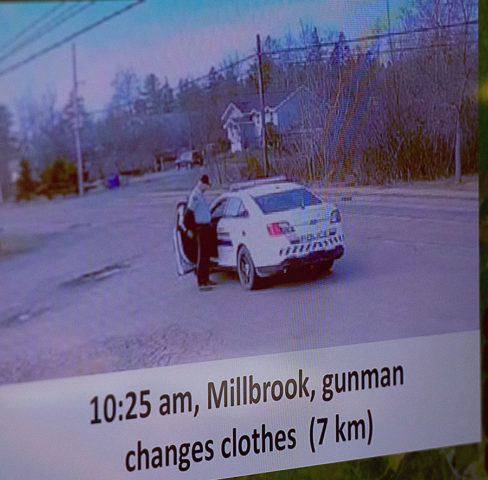

But the two Mounties were wrong. At about 10:45 p.m., 20 minutes after the first officer arrived at the scene, the gunman escaped by driving along a little-used dirt road beside a blueberry field.

“That didn’t show up on the map we were looking at,” Carroll said afterwards.