Manisha Krishnan

November 3, 2021

-Vice

For nearly five years, Daniel Garrett made two-hour round trips, sometimes twice a day, from Martin to Jackson, Tennessee, so he could buy heroin, anywhere from half a gram to a gram each time.

The rides, along a highway that passed through a string of small towns, often took place at night, which was dangerous because of the failing headlights on his 2007 black Nissan Sentra and because Garrett made the trips home high; one time he nodded off, crossed over a median, and skidded 200 feet.

Finally, this March, the 26-year-old copywriter moved to Jackson to be closer to the source of the drugs he wanted. But once there, he noticed heroin was becoming harder and harder to find. Then it disappeared altogether.

“I saw it pop up maybe three or four times, but for no longer than three or four days in a row,” Garrett told VICE News.

He hasn’t come across any heroin since September—it’s been entirely replaced with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that’s up to 50 times more potent.

“Fentanyl sucks,” Garrett said. “It doesn’t last long, it doesn’t provide you much euphoria, so it doesn’t offer me much utility. It’s just fentanyl around now, and I fear it’s going to be like that forever.”

According to the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, the state’s heroin supply is increasingly being contaminated with or replaced by fentanyl, which was behind 66 percent of fatal overdoses in 2020. It’s a trend that extends to many former heroin strongholds in the U.S., including Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Ohio, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, as well as neighbouring Canada.

“Most of the Eastern states, for the past several years, it’s been very difficult to get much heroin at all and a lot of the times it will just be pure fentanyl,” said Dr. Ryan Marino, medical director of toxicology and addiction medicine at University Hospitals in Cleveland.

“Is this goodbye to heroin?”

Once one of the most popular—and notorious—illicit opioids, heroin is disappearing from drug markets across North America. In some places where it was once widely available, like Vancouver, British Columbia, dealers and users told VICE News there’s no heroin to be found. And they want it back, not just because it’s their drug of choice but also because its replacement—fentanyl—is killing people in droves. Meanwhile, drug users who’ve shifted from using heroin to fentanyl are seeing their tolerances increase, making it harder to switch back, even if that’s what they desire. Some users are calling for a heroin renaissance of sorts—they want a legal exemption to source and use it—before it’s too late.

Once one of the most popular—and notorious—illicit opioids, heroin is disappearing from drug markets across North America. In some places where it was once widely available, like Vancouver, British Columbia, dealers and users told VICE News there’s no heroin to be found. And they want it back, not just because it’s their drug of choice but also because its replacement—fentanyl—is killing people in droves. Meanwhile, drug users who’ve shifted from using heroin to fentanyl are seeing their tolerances increase, making it harder to switch back, even if that’s what they desire. Some users are calling for a heroin renaissance of sorts—they want a legal exemption to source and use it—before it’s too late.

“We are missing the opportunity. It is going by so fast,” said Erica Thomson, executive director of British Columbia and Yukon Association for Drug War Survivors, a drug user advocacy group. “Is this goodbye to heroin?”

People like Garrett and Thomson have their reasons for favouring heroin, including its vinegary smell, its taste, and the feeling of “euphoria” it can create.

But there are pressing reasons why its scarcity is wreaking havoc. Primarily, that it’s much easier to overdose on fentanyl.

“The old-school people, if people get their hands on heroin… people tend to want that. They’re like, ‘That’s the old-school stuff, that’s the safe stuff,” said Keisha, 32, a B.C.-based fentanyl dealer who’s been in the drug trade since she was a teenager.

“Even though it doesn’t work for them, it’s the thought of it being there. If you’re an IV user, it’s the taste or the feeling. If you’re a snorter, it’s the smell and the euphoric feeling afterwards. And it’s safe to use—people think of heroin: that’s safe.”

But the idea that heroin is “safe” is relative. It’s linked to thousands of fatal overdoses a year in North America, though drug policy reform proponents would argue that prohibition is the problem rather than the substance itself.

“Heroin is something that’s been used in this country for over 100 years. It has been illegal since the 1920s, but rates of heroin use in the United States have kind of remained pretty much the same over that time period and we never saw overdose rates approaching what they are now,” Marino said.

“[Heroin] overdoses would be in the thousands every year, which is still bad and requires work. But seeing now almost 100,000 Americans died last year from overdoses, and that’s primarily from fentanyl.”

Developed in the late 19th century in England and used to treat respiratory illnesses like tuberculosis, heroin was initially marketed as a wonder drug in the medical community, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

“Heroin was always advertised as the world’s most potent painkiller,” said Neil Boyd, a criminologist at Simon Fraser University.

At the 1909 Shanghai Opium Commission, nations including the U.S., the UK, and Germany passed a number of resolutions designed to stamp out smoking and smuggling of opium and its derivatives. (Heroin is a derivative of the morphine alkaloid in opium.) It was a harbinger to the war on drugs, according to Boyd.

“Britain at the time was all in favour of regulation. America took this moral approach and they basically got their way, so the entire world has been subject to this unregulated, criminalized system of distribution,” Boyd said. The U.S. officially banned heroin in 1924.

“You look back to 1890 in British Columbia, where there were smoking opium factories in Vancouver, Victoria, and New Westminster. If that had been allowed to continue, maybe we never would have gotten into the mess that we’re into today,” he said.

“There was an attraction to it. You were sort of pushing boundaries. You were exploring new horizons.”

According to Boyd, heroin’s popularity in North America began taking off in the 1950s and 60s. It was used by a number of classic rock artists, including members of the Rolling Stones during their “Exile on Main Street” getaway to France, and was the subject of songs by Neil Young and The Velvet Underground, among others.

“Heroin was, I know from people who were in the music in the 60s and 70s—there was an attraction to it. You were sort of pushing boundaries. You were exploring new horizons,” Boyd said.

In the 1990s, Vancouver recorded a rise in heroin overdoses, leading to the creation of Insite, North America’s first safe injection site in 2003; the drug also ravaged the grunge scene in nearby Seattle. In the early 2000s, fatal heroin overdoses spiked in the U.S., with death rates quadrupling from 2002-2013; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention attributes that in part to an increase in painkiller prescriptions. The chances of overdosing on heroin increase greatly when the drug is injected intravenously.

Heroin has been linked to the deaths of celebrities Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Layne Staley, Kurt Cobain (who was reported to be high when he died by suicide), Cory Monteith, John Belushi, Janis Joplin, and River Phoenix—although often in conjunction with alcohol or other drugs—giving it a reputation as a dangerous drug that was not to be used recreationally.

“Most people don’t become dependent on it. So that’s one of the mythologies that’s built into it,” Boyd said. “But when people do, it can be very difficult.”

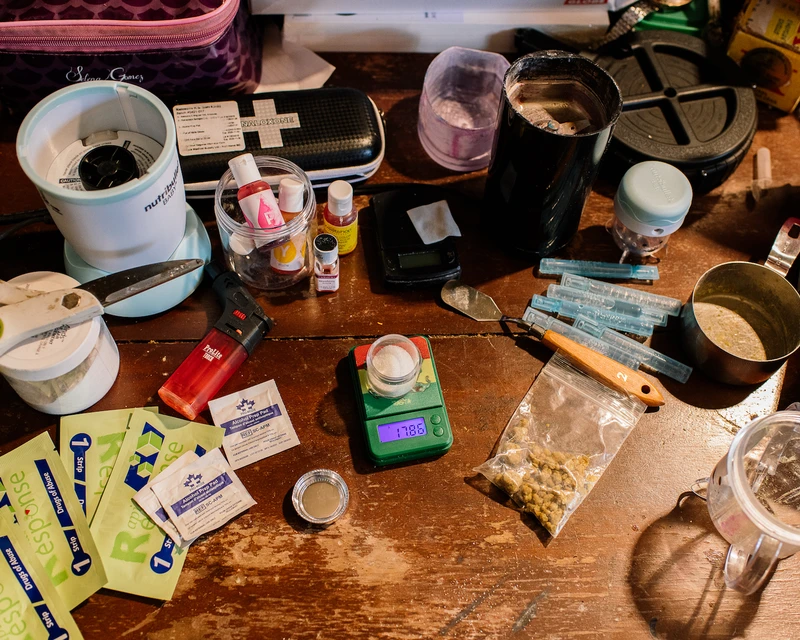

Located in Abbotsford, B.C., about an hour and a half east of Vancouver, Keisha’s beige rancher has a crossbar (and occasionally a friendly Doberman) guarding the door and a black gate that can lock off the hallway leading to two bedrooms. Harm reduction supplies are dotted about every room, including stashes of naloxone, fentanyl testing strips, syringes, pipes, and blue tourniquets for injecting drugs. In Keisha’s room, amid Marilyn Monroe posters on the walls, a large display of security cameras monitor various areas of the house. VICE News is not using Keisha’s last name because she sells drugs.

Sitting in Keisha’s living room eating a slice of pizza, Thomson, of the Drug War Survivors, told VICE News she began using opioids again about two years ago after eight years of abstinence. She said she was triggered by dealing with the steady stream of family and friends overdosing on fentanyl.

“I needed a vacation and I couldn’t take one. So I did it the next best way, which was to buffer my heart and be able to continue putting one foot in front of the other instead of winding up in my bed with the blankets over my head,” said Thomson, 46, her hair a shock of orange-red and glitter adorning on her face.

As she gave the interview, she guarded Keisha’s door; a steady stream of customers, some purchasing fentanyl, others crack cocaine, streamed in and out of the house all day. The women have been friends for years.

Thomson believes people use drugs for different reasons, including resiliency to get through trauma. At times, her voice caught as she discussed the hardships she’s faced over the years, including losing custody of her baby daughter for a few months.

“She said it reminded her of waking up with Grandma’s apple pie on Christmas morning.”

She’s pushing the B.C. government to give drug user groups like hers exemptions so that they can create heroin compassion clubs, allowing them a clean supply of heroin that could then be distributed among members and consumed—potentially in a lounge—free of criminal sanctions. She already tested a pilot version of the project three years ago with around eight people.

“I had found a source for a very good price and it was perfect old-school heroin,” she said. “It worked out to about $7 a point [0.10 grams] when we put all of our money into it instead of $20 a point, so that was a significant difference.”

She said people start “reminiscing” when they taste real heroin. One woman in the pilot group cried.

“She said it reminded her of waking up with Grandma’s apple pie on Christmas morning.”

But Thomson said once word got around that the group had sourced proper heroin, her supplier’s price went up by $900 (US$730) to $2,800 (US$2,200) an ounce. She’s had trouble finding a source since then.

Keisha said she can find any drug, but old-school heroin is among the hardest to come across from her various suppliers.

“It’s almost hidden away. You have to really dig for it,” she said.

When she’s able to find it, it often has a hefty price tag, as high as $4,200 an ounce. Raw fentanyl costs her about $500 for a “ball,” which can then make an ounce, once it’s diluted with buffers. A point of fentanyl is $20—a point of heroin these days would be at least that, though heroin would last around six to eight hours; with fentanyl, depending on a person’s tolerance, they may want more in a couple of hours.

Because fentanyl is shorter-acting than heroin, users need more of it more often to avoid getting dopesick (e.g., withdrawal).

Both Keisha and Thomson said what’s sold on the street in B.C. as heroin is usually just fentanyl now—and that some people don’t even know what they mean when they talk about heroin.

“They think I’m talking about pure fent,” Thomson said.

She said it’s disturbing to see people essentially turn into zombies when they’re on fentanyl, especially as the supply in B.C. is increasingly being cut with benzodiazepines, or tranquilizers.

“People fall asleep no matter what they’re doing—it could be trying to cook, drive,” Thomson said. The withdrawal from fentanyl is also more gruelling on the body.

Thomson said she’s been trying to stick to using the prescription painkiller Dilaudid and morphine, but she sometimes has to supplement with fentanyl.

She believes fentanyl users could wean back onto heroin even though heroin is far less potent. But the longer it’s unavailable, the harder it will be to achieve that. When she conducted an informal survey of local drug users, 29 of 30 people said they would switch back to old-school heroin if given the chance.

Vancouver’s Providence Crosstown Clinic was the first clinic in North America to prescribe medical-grade heroin (diacetylmorphine) as well as hydromorphone. The program, which serves around 130 people, sources the drug from Switzerland via the Canadian government. It’s considered a last-resort treatment for people for whom methadone and other therapies haven’t worked: studies have shown it can be beneficial in improving health and well-being and reducing criminal activity to pay for drugs.

Thomson believes drug user groups should also have access to heroin sourced either from abroad or produced locally. (She said the dark web is also an option, although less desirable because it lacks the relationship-building you’d have with other suppliers.) She said she would want the model to be community-based, giving drug users and sellers agency and making use of their expertise. It would also be a chance to educate people on harm reduction, she said.

“It’s actually so beneficial in many ways,” said Thomson. “Where you’re going to limit criminal activity if you’re able to access substances at a lower cost… the government knows there needs to be access to safe supply. They know that that will reduce overdoses.”

Experts say once it’s gone, it’s unlikely heroin will make a comeback in a serious way. Because fentanyl is synthetic, unlike heroin, which comes from poppies, it’s cheaper and simpler to make or import, and to turn a profit off due to its potency. Plus, fentanyl’s chemical structures can constantly be tweaked to create new fentanyl analogs—drugs that mimic the effects of fentanyl but can be even more powerful and can evade government-banned controlled substances.

University of Calgary biochemist Peter Facchini runs one of the only labs in the world dedicated to researching opium poppies.

Facchini said to make heroin, you need morphine, but there’s not much import of illicit morphine into Canada, so generally heroin is imported here in its final form. As for growing poppies to make heroin, “a thousand opium poppy plants doesn’t give you an awful lot of morphine to make enough heroin. You need hectares of plants growing. It’s not going to be possible to hide it,” he said.

Facchini said Europe’s heroin markets have likely remained intact because there’s a land bridge between Europe and Afghanistan, the source of the morphine.

“It just comes down from an illicit point of view to accessibility and economics. Fentanyl is easier to import from China,” he said.

While he supports the idea of a safe supply for people addicted to opioids, he said a long-term solution should be developing painkillers that don’t have addictive properties.

“As far as I know, there’s no pharma companies that are working on alternatives to opioids or opiates that have improved properties that would be highly effective but not addictive.”

Garrett said he has considered moving to the West Coast or the Midwest, where he can still find heroin, but he doesn’t want to leave behind his harm-reduction efforts in Tennessee. He spends his spare time running an underground syringe-exchange program and carting naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and other drug paraphernalia around his car and offering them to drug users at hotels. He said he’s overdosed at least three times on a combination of heroin and fentanyl, though he blames that in part due to stress from legal issues tied to his drug consumption.

Garrett said heroin helps him cope with his anxiety and depression, “but on top of it, it just makes me feel good.”

He’s currently enrolled in a methadone program that requires him to go to a clinic daily and complete urine tests. He said his dose isn’t high enough to completely divert him from using fentanyl. Ironically, he said the clinic told him if he keeps testing positive for street drugs, he’ll be cut off.

“That’s an ass-backwards way of thinking, because I want enough legal methadone to not use illicit opioids.” In an ideal world, he said he would have access to legal painkillers like oxycodone or morphine.

He said he knows he will use drugs for the rest of his life and it frustrates him that he’s being criminalized for it.

“I feel like opioids improve my life holistically. I really think they do. And maybe that’s funny because, you know, it really puts me at high risk of death.”