Updated:April 29, 2022

-CBC

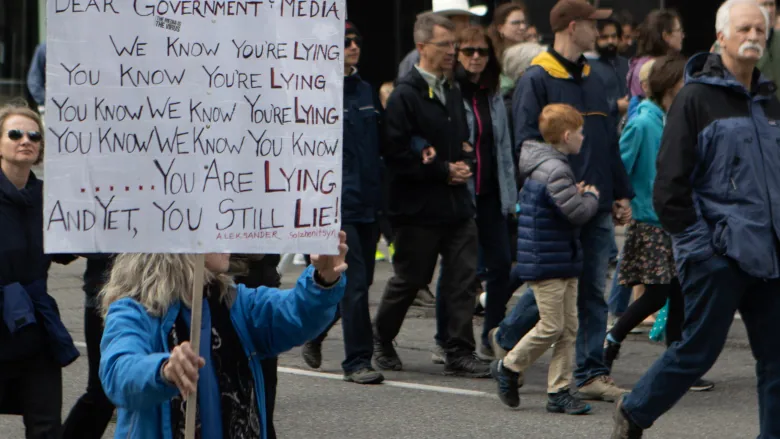

A quarter of Canadians believe in online conspiracy theories, an expert on radicalization and terrorism told a parliamentary committee Thursday.

David Morin, a professor at the Université de Sherbrooke, said a poll conducted for an upcoming report he is preparing for the Quebec government found that 9 to 10 per cent of Canadians strongly believe in conspiracy theories, while another 15 per cent moderately believe them.

Morin told members of the public safety and national security committee that some of those who believe conspiracy theories — “but not all” — have “a sympathy towards violence.”

The poll, run by the Léger marketing firm, was conducted online from May 19 to June 6, 2021 with 4,500 respondents over the age of 14. A comparable margin of error for a probability sample of the same size would be +/- 1.5 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

The poll asked 33 questions, including questions about pandemic conspiracy theories.

The report is to be delivered to the Quebec government in the coming weeks.

Morin’s testimony came as the committee continued its study Thursday of Ideologically Motivated Violent Extremism (IMVE) in Canada.

Morin, who was named last month to a federal government advisory group on rules to address harmful content online, said IMVE is a complex phenomenon driven by factors that converge and diverge, including far-right extremism, anti-government movements, misogyny and conspiracy theories.

Morin said there has been a 250 per cent increase in violent demonstrations in Western countries over the past five years. Canada saw a 25 per cent increase in hate crimes in 2020.

The changing nature of far-right extremism

Morin said there are a number of reasons for the increase in polarization: a loss of confidence in institutions and the effect of social media and alternative media, as well as local and global contexts such as the pandemic, economic crises, migrant crises and climate change.

The nature of right-wing extremism has also changed over time, Morin said. Decades ago, he added, far-right extremists might have been neo-Nazis.

“The far-right has evolved,” said Morin. “The far-right today is also people in suits and ties.”

The far-right has also adopted a populist tone, presenting itself as a movement defending ordinary people from the elites, Morin said.

Morin said it would be a mistake to underestimate the risk of IMVE or to take the health of Canadian democracy for granted.

“Doing nothing is no longer an option,” Morin told MPs. “What to do is another problem. History teaches us that it is majorities and not minorities which topple democratic regimes.”

Morin also warned politicians about the dangers of partisanship and attempts to score political points over the threat of extremism.

“It is like walking around with matches in a dynamite warehouse,” Morin warned.

Intelligence agencies should infiltrate the far-right: Morin

Morin said misinformation and disinformation are a major problem and countries looking to interfere with rival nations use social media to exacerbate existing divisions in society.

He said regulations are needed and while the government has monitored potential foreign interference in elections, Morin said it should also extend that monitoring to the period between elections and do more to educate Canadians.

Morin also recommended that Canada’s intelligence agencies reinvest in infiltrating far-right extremist groups.

Carmen Celestini, a post-doctoral fellow with Simon Fraser University’s Disinformation Project, told the committee that conspiracy theories play an integral role in social political movements and the spread of extremism.

“QAnon has leapt from the online world to violence in the real world and is, at present, a global phenomenon,” Celestini told MPs.

“The conspiracy is spread predominantly through social media platforms. Adherents of QAnon conspiracy are not limited to a geographic range, with adherents and supporters found globally, including Canada.”