December 21, 2021

-News.com.au

Forests of antennas are popping up across the South China Sea. And they’re further evidence of Beijing’s determination to dominate the strategic international waterway.

Metal poles with wires strung between them seem harmless enough. Even a cluster of big satellite dishes isn’t all that uncommon anymore.

But it’s what they’re attached to that counts.

International affairs think-tank the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) warns Beijing is “taking major steps toward improving its electronic warfare (EW), communications, and intelligence-gathering capabilities near the South China Sea”.

And that means potentially turning the contested waterway into a communication and navigation “dead zone”.

Recent satellite imagery reveals that China has made major improvements to its electronic warfare, communications, and intelligence gathering capabilities near the South China Sea through the rapid expansion of facilities on Hainan Island.

Learn more: https://t.co/XG3oyD0mOv pic.twitter.com/mhlFv1v7MQ

— CSIS (@CSIS) December 20, 2021

The battle to dominate the region’s electronic spectrum has already begun.

Last year, a Chinese news report claimed a US combat aircraft “lost control” while flying over the South China Sea. “All the instruments in the cabin were chaotic,” the report claimed. “The fighter planes were completely out of control and could not communicate with the outside world, but they did not know what happened.”

The claim appears to relate to a 2018 incident in which US Navy EA-18G Growler aircraft from the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt reported jamming of their equipment. Pilots, however, said they were never put in any danger.

But Beijing certainly appears to have been determined to build up its ability to do precisely that.

“The war of the future will not only be about explosions, but will also be about disabling the systems that make armies run,” a recent Brookings Institution report warns. “We could see effects as stodgy as making a tank impossible to start up, or sophisticated as retargeting a missile midair.”

Electronic combat

It’s aggressive. But it’s not physical. So that puts attacking another nation’s ability to navigate and communicate into something of a legal and diplomatic ‘grey zone’.

CSIS reports China’s artificial island fortresses at Subi and Fiery Cross Reefs in the South China Sea feature extensive communications and intelligence gathering facilities. There’s also a network of sensor towers between Hainan Island and the Paracel Islands.

They’re ideally placed to detect, monitor – and interfere with – any electronic activity in the region. And that means vital equipment may not perform as expected.

Drones could be hacked. Navigation signals could be distorted. Datalinks could be hijacked.

Communications could be both intercepted and jammed.

This means combat aircraft may not find their targets – whether that is a refuelling tanker or a hostile warship. Drones may turn upon their owners. It could break the complex web of data sharing that’s supposed to make modern weapons, such as the F-35 stealth fighter, overwhelmingly effective.

And any digital device may be hacked.

“Our military systems are vulnerable,” the Brookings report warns. “We need to face that reality by halting the purchase of insecure weapons and support systems and by incorporating the realities of offensive cyberattacks into our military planning.”

High tech equipment won’t just be disabled. Its functionality can be subverted.

“It’s not that bases will get blown up; it’s that some bases will lose power, data, and communications,” the report reads. “It’s not that self-driving trucks will suddenly go mad and begin rolling over friendly soldiers; it’s that they’ll casually roll off roads or into water where they sit, rusting, and in need of repair.”

The potential is for a pre-emptive strike that disables a nation’s ability to fight.

“Gone are the days when we can pretend that our technologies will work in the face of a military cyberattack. The future of war is cyberwar. If your weapons and systems aren’t secure, don’t even bother bringing them onto the battlefield.”

Mumian: ‘Grey zone’ fortress

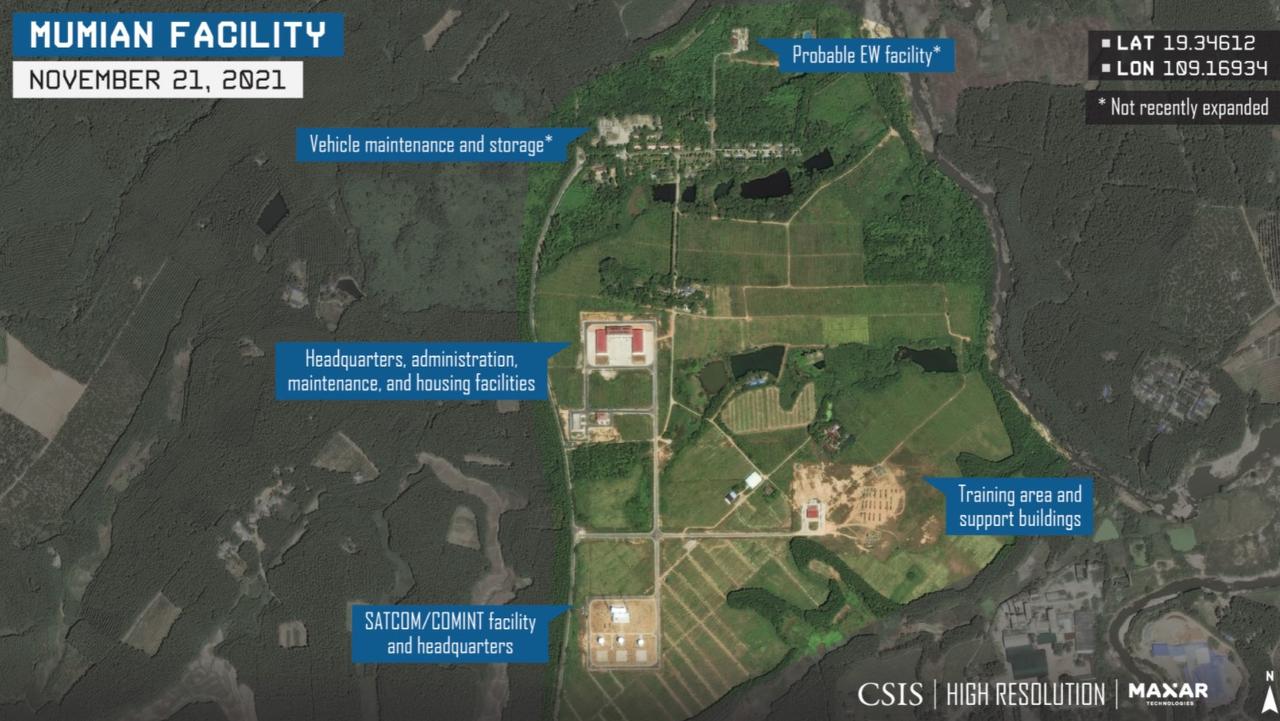

Satellite images of China’s island fortresses in the Spratly and Paracel Islands have revealed the presence of large arrays of antennas and satellite dishes. Now China’s been seen rapidly expanding facilities near a town called Mumian on Hainan Island.

It’s a battle on many electronic fronts. It’s a domain co-ordinated by China’s Strategic Support Force (SSF).

Their sensor arrays can detect, record and analyse any transmission – such as radar – in the region (SIGINT, signals intelligence). They can attempt to decipher intercepted communications (COMINT, communications intelligence).

They can track and communicate with satellites (SATCOM). They can blast targeted areas of the radio spectrum with raw energy to jam signals and the operations of specific electronics (EW, electronic warfare).

They can manipulate the data being transferred over the airwaves (cyberwar).

The Mumian facility was built in 2018. But fresh satellite imagery reveals it has undergone rapid expansion in recent months.

A new array of four dish antennas track and communicate with satellites. And the site’s tower farms – which can receive or transmit – has also doubled in size.

Most significantly, however, is the construction of a large new headquarters and barracks facility. And scattered throughout the facility are some 90 vehicles, many carrying their own antennas.

“Most of the recent expansion was completed in a little over a year,” The CSIS report states.

“While significant in their own right, the upgrades at Mumian are part of a broader effort by the PLA to shore up its defensive and offensive electronic capabilities.”