July 21, 2021

-The Federalist

PORTLAND, Ore. — No state is more emblematic of deepening political and cultural divisions in America than Oregon, where a movement is underway in the state’s more conservative southern and eastern counties to break away from the radically leftist urban centers in the northwest and become part of an enlarged Idaho.

Such efforts have been around for decades as divisions sizzled under the surface. Each side sees the other with a growing contempt, as leftists in the state capitol, Salem, rule with a legislative supermajority and, increasingly, no regard for their neighbors in largely rural eastern Oregon. In that part of the state, the imposition of what many consider to be alien values has met increasing resentment and now, proposed separation.

“The Oregon legislature is not listening to rural Oregon’s representatives or senators,” Mike McCarter, the founder of Move Oregon’s Border told The Federalist at the proposed boundary along the Deschutes River in LaPine, 170 miles from Salem. “They don’t have to… so they’re just doing their own agenda.”

That agenda, whether it comes from the governor, legislature, or ballot initiatives, is dictated by the 78 percent of Oregon’s population living on 21 percent of the land, crafting policies that better fit the needs and culture of the northwest urban metropolis, anchored by Portland, as opposed to the small, conservative towns that dot the rest of the state.

The agenda includes decriminalization of hard drugs and prostitution, alongside a growing push to criminalize hunting and cattle ranching. It includes cannabis and liquor stores deemed essential while churches are shut down. It includes stricter laws for dealing with the homeless, with a greater burden placed on those who seek their removal. And it includes harsh new gun control measures with new bills passed just last month restricting firearm storage. All of these things come amid dismissed objections from the rest of the state.

Portland and Salem ruling over rural Oregon is like California governing Kansas. Many residents out east feel this situation gives them state representation in name only.

“They’re limited to just not enforcing the laws, they can’t stop the laws,” McCarter said about the situation.

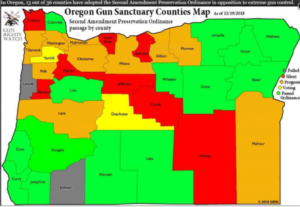

Nonenforcement is exactly what many counties have opted to do, with at least 14 jurisdictions declaring themselves “Gun Sanctuary Counties,” according to the Gun Rights Watch, where local law enforcement has pledged not to enforce new gun restrictions from the state legislature.

McCarter emphasized the movement is not a campaign to carve out a new state, arguing such an effort would generate overwhelming political barriers because it would mean the addition to the U.S. Senate of two Republican senators. Neither Oregon’s Democrat-controlled legislature nor the D.C. political establishment would ever approve of such a scheme. Demands for a new state could also make the campaign to move Oregon’s borders appear disingenuous, he noted, as a mere power grab rather than a plea for self-governance and representation.

Leftists who mock the campaign, meanwhile, are in pursuit of a state border transformation of their own in the effort to grant D.C. statehood, and with it, the addition of two new Democratic senators. In April, House Democrats passed legislation to do just that. They have openly discussed the same for Puerto Rico, for the same nakedly partisan reasons.

Puerto Rico has a population of more than 3.1 million. D.C.’s population is nearly 700,000, and the total population of the east Oregon counties hoping to join Idaho is just more than 800,000.

Movement For Greater Idaho Picks Up Steam

Talk of Idaho adopting a handful of eastern Oregon counties has existed for decades. But the idea has only recently picked up steam as political polarization in America has deepened, exacerbating the drive to separate, complemented by some attention from the corporate press and the recruitment of respected operatives to spearhead the campaign.

Mark Simmons, who served as one of Oregon’s last Republican House speakers from 2001 to 2003, joined McCarter in the crusade this year.

“Some will consider it a long shot, but defeating the British was a long shot,” Simmons told The Federalist, invoking the American fight for independence with complaints about “lack of representation” in Salem.

But the idea isn’t just bluster. Simmons said induction into Idaho and separation from Oregon would be best for all parties, arguing the regulatory framework in Idaho, which is far more conducive to rural ranchers and farmers, better suits the needs of the population than the burdens of Oregon’s heavy administrative state. Oregon wouldn’t have to pay for rurally dispersed services, and Idaho would benefit from the expansion of the tax base with a bureaucracy established to meet east Oregon’s particular needs.

The proposal envisions a “greater Idaho,” and seeks to move 18 counties and portions of three more into Idaho, as well as several counties in northern California with similar grievances about that state’s Democratic supermajority in Sacramento.

The strategy, McCarter said, has been first to go county by county and open discussions with local state lawmakers. In May of this year, five counties voted by wide margins to join two others that in November gave a green light to the process.

The movement, McCarter said, has drawn support from Idaho lawmakers who appeared at a rally in Boise earlier this month.

“I’m open to the idea as a legislator,” Idaho Republican Rep. Bruce Skaug, who was at the event, told The Federalist. “I want to have the conversation.”

Idaho Rep. Barbara Ehardt, another Republican who was there and chairs that state legislature’s Environment, Energy and Technology Committee, organized a hearing on the issue in the state’s lower chamber, She told The Federalist Idahoans would be unwise not to consider it.

“Why wouldn’t we want to have that conversation with people who share like-minded values?” she said, emphasizing the importance of self-governance. “They have every right to seek redress from another state government that upholds the Constitution.”

Two Different Worlds With a Shortening Fuse

The contrast between the culture and lifestyle of those in eastern and western Oregon becomes immediately apparent once you cross the Cascades.

Holly Guardado is a Louisiana native who has worked as a marijuana dispensary manager in the City of Bend for five years, at the crossroads of east and west Oregon. Sipping a beer on a Monday night in a local sports bar, Guardado, a millennial lover of the outdoors and electronic dance music (EDM), sat with tattoos lining her right forearm and black hair tinted green. When the bartender said the community was home to a “hippieish vibe,” Guardado came to mind.

“The difference between each side of the Cascades is night and day,” Guardado said, highlighting face masks as the most visual current symbol of cultural identity. Anywhere west of the mountains, she said, and she feels naked without one. Anywhere east, she hides it in her bag.

Guardado added that she had seen a transformation in Bend just within the half-decade she’s lived there. What used to be a town of fewer than 20,000 people 20 years ago is now a bustling community of more than 100,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, where traffic often jams streets built for a smaller population.

Located at the center of the state, where east and west meet, it’s common to see cattle ranches sporting Donald Trump signs along their fences across from neighbors who’ve posted social justice signs on theirs. The city, with majestic views of the Cascades and easy access to nature trails and ski resorts, has clearly become another story of pandemic transformation, where the work-from-home revolution has brought a flux of new residents — and with it, wealth and liberal politics.

The changes pushed Theresa Luft out of the town she grew up in last winter. After living 40 years in Montana, Luft returned to Bend in May. But by December, she’d left.

“It’s not the same place it used to be,” Luft told The Federalist while seated at a shaded picnic table in her new hometown of Baker City, 60 miles from the current Oregon-Idaho border along the Snake River. The town has a population of fewer than 10,000.

Luft said the migration from western Oregon’s Willamette Valley into Bend was overwhelming, and changed not only the city’s pace, but its culture into that of a Portland suburb. She linked her move to her political roots: “I’m a Republican, what can I say? I don’t believe in what’s going on.” Even a visit to downtown Portland, she said, made her “nervous.”

“The Democrats are giving Oregon a bad name, I think, because when you say you’re from Oregon, they think of Portland,” she said. “And I’m pretty embarrassed by it myself.”

Luft is far more comfortable living in eastern Oregon, where the rural half of the state is more similar to Idaho than the ruling-class communities west of the Cascades. The agricultural economies are similar, the politics are similar, the cultures are similar. Even the towns look similar.

Voting patterns in the 2020 election underscore the political ties of the region, and clearly show eastern Oregon’s disconnect from its western rulers. The redder the county in the map below, the greater the share of the vote that went to Trump. Although data for Idaho from the map below is missing, the state went for Trump by 30 points.

One practical result of these divisions is the geographical clustering of people who share similar values. When elites impose radically different values on a large swath of the population that is tied to their land, communities may become ungovernable. Luft was able to move around as she pleased, but it’s far more difficult for a rancher to do the same.

Last year, violence broke out between dueling demonstrations in Bend, where tensions between the leftist west and conservative east are fraught.

Punches, taser, mace. Bend demonstrations turn violent after someone snatches a trump flag pic.twitter.com/gzTCbATWcv

— Emily Cureton (@emilycureton) October 3, 2020

Oregon’s escalating episodes of political turmoil and violence have marked it as one of the epicenters of the American crisis. Antifa rioters, declared domestic terrorists by President Donald Trump’s former Acting Homeland Security Chad Wolf, held Portland’s downtown city center under siege for more than 100 consecutive days last summer.

The carnage left east Oregon’s population in horrified awe of what the state’s largest city tolerated. Residents in Baker County told The Federalist if Antifa militants showed up on their doorsteps, vigilante justice would ensue.

Meanwhile, the far-right takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge five years ago marked another inflection point in the state — and nation’s growing divide. In 2016, east Oregon ranchers led by Ammon and Cliven Bundy occupied the refuge half a decade before Antifa took over Seattle. While the dispute focused on tensions over state and federal land use, with legitimate frustrations under the surface, the demonstration showcased elements of extremism prevalent on both sides of the Cascades — and a growing fissure.

McCarter, however, clearly distanced the non-partisan movement for a Greater Idaho from the Bundy episode.

“We’re not in favor of the Bundys,” McCarter said, seeing them as grifters who capitalized on the publicity afforded to them by corporate media.

Antifaland

Portland is a beautiful city. Mount Hood’s majestic peak pierces the horizon in the eastern sky. Lush Pacific Northwest greenery surrounds the city and graces its downtown buildings, woven throughout the urban landscape. The Willamette River glitters in the sunlight as it flows into the Columbia on the Washington border.

Portland is also a leftist paradise, which in practice means homeless tent encampments have overtaken the city. Local officials have passed new edicts to make their removal more difficult, offering a haven to the homeless nationwide.

Taxes are high, the cost of living is high, wealth inequality is high. Protests, meaning riots, are common among ultra-woke urbanites protesting their own progressive leaders. Businesses remain boarded up, if not shut down for good. And two months after the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) relaxed face mask recommendations, they remain in use everywhere, even outside. Oregon lifted its statewide mask mandate two weeks ago.

I stopped one woman who was wearing a cloth facial covering at a street corner to ask why she was still wearing a mask.

“I don’t trust other people,” she said.

“Are you vaccinated?” I asked.

“Yes.”

Before I could ask if she trusted the vaccine, she walked away.

Another woman who was wearing a surgical mask outside was more candid about the device as a matter of convenience.

“Because my face is messed up,” she said, and left it at that.

I lost count of the number of times I spotted human feces on the sidewalk. I began to watch my step after the second, as if I were walking around the yard of someone who had a dog.

The aura of leftism in Portland is distinct upon entry. People dress differently. Sometimes a person’s sex was difficult to detect. A few men downtown wore dresses. Murals for social justice dotted the city, and signs professed small business loyalty to the cause — if they survived the constant riots of the last 15 months. The street corner below used to be a 7-11 before it was torched by anarchists.

In other words, Portland could not be more different than the eastern counties it shares the state with. And yet, the population in Portland is the population in power.

Obstacles Spark Skepticism

The three-seat Baker County board of commissioners met in a special session last Wednesday to discuss the ambitious proposal to move Oregon’s borders. McCarter spoke to the board through Zoom, with nine residents in attendance at the local courthouse, including Luft.

“I think all of us know that most rural Oregonians are very frustrated with Oregon’s leadership and the Oregon legislature not listening to our state senators or our representatives about our issues,” McCarter told the group.

His remarks fell on a sympathetic audience, where the three commissioners each shared McCarter’s frustrations but voiced practical concerns.

“There is a very large disconnect between that part of the state to this part of the state… they do not understand how we think, function, [or] act,” Commissioner Chairman Bill Harvey agreed.

Commissioner Mark Bennett said he was unsure how the campaign would convince the Oregon legislature to approve the proposal. For the counties to be adopted into Idaho, those who want to move have to approve the plan on their own, and then pass the plan through both state legislatures, and finally through Congress.

“At the end of the day, Idaho can vote yes, we can all vote yes, and then three counties— four probably, for sure four, can dictate the course of the empire,” Bennett said.

Oregon Republican Sen. Bill Hansel, who represents Sherman County (which voted 429 to 260 in favor of “promoting moving Oregon-Idaho border”) told The Federalist the obstacles made the probability slim, “but not impossible slim.”

“I can understand why there is that movement,” Hansel said of the campaign to move his own district into Idaho, and compared the sentiment to that of British colonists nearly 250 years ago.

“When you’re frustrated with the government you have for whatever reason, you look for opportunities, and this realigning statehood would be one of them,” Hansel said. The senator noted, however, the only time borders have been dramatically changed in a similar manner had been at the height of the Civil War, when 39 counties formed West Virginia.

Republican Rep. Mark Owens, who represents Baker and Malheur Counties, both of which voted to break off, told The Federalist he wanted to travel to Idaho and probe interest among the neighboring state’s lawmakers before he considered the proposal seriously.

“I’m not ready to give up on Oregon,” Owens said. “My first goal is to try to figure out how to make Oregon the place we want to make it.”

An alternative solution, Owens proposed, was to reform the state senate into districts decided by geography as opposed to population, more similar to the upper chamber’s structure in Congress.

“We need to stop looking at the other party as the enemy and figure out how to work together,” Owens said, emphasizing a reduction of polarization was his preferred forward pathway.

Oregon Democrats have yet to show any interest in even discussing the proposal for an amicable separation. No members of the statehouse leadership returned The Federalist’s multiple requests for comment.

Oregon’s Future Is the Nation’s Horizon

At a time comparisons to the 1850s abound, with a new administration ushered in at a volatile moment of historic political polarization, the real story of America’s crackup is playing out quietly in places like rural eastern Oregon

The United States won’t likely see an 1862-style Civil War with armies and tanks mounting a full-scale revolution. President Joe Biden made that clear last month when he bizarrely celebrated American independence with a pledge to put one out with nuclear weapons.

But what America could see on the horizon, and might already be seeing, is the Balkanization of the country, with regional campaigns to re-impose self-government by reimagining the states in order to maintain the union through governable separation. It might lack the pathos of a charge on the U.S. Capitol, but it might actually save the republic.

“One of the things that people say is, ‘Oh, this can’t happen,’ and when we’re looking backwards, they’re probably right,” Ehardt told The Federalist. “But if we look where we are right now and are looking forward, I absolutely believe that this is not only likely to happen in Oregon but that it will also happen in the rest of the United States.”